“All the presents that I have sent, or caused to be sent forth unto you, must be used in a proper line of sensation, for they are all spiritual….They have been sent forth in this degree of nearness and semblance of material things that do exist on earth, that you might be better able to appreciate in lively colors, and thrilling sensations, the real adornings and beauties of the spiritual world”

Philemon Stewart, “A Closing Roll from Holy and Eternal Wisdom.” 1843

According to Shaker belief, these words were spoken by Mother Ann Lee, the founding leader of the Shaker religious sect in the United States, in 1843. In 1843, Lee had been dead for fifty-nine years. Her active communication with Shakers in the mid-nineteenth century was enabled by “Instruments”: community members who, like Brother Philemon Stewart, were able to receive dispatches from a world of spirits populated by the dead and the divine. These interactions across realms took the form of verbal or textual pronouncements as well as dances, songs, physiological responses, and vivid visions. Often incorporating “lively colors and thrilling sensations,” as mentioned in Stewart’s testimony, visions were recorded in extensive written accounts and, more rarely, through exuberant watercolour, pen, and ink representations known as “gift drawings.” Produced by mostly female worshippers from 1837 to the late 1840s, gift drawings erupted out of a strictly aniconic culture rooted in the pursuit of simplicity, introspection, and withdrawal from worldly pleasures. Gift drawings, by contrast, featured swirling polychromatic patterns; ludic, illegible mark-making; deliciously corporeal renderings of jewelry, fruit, furniture and clothing in colors like pink and gold. As manifestations of the visions received by Instruments, gift drawings were vehicles for the sensory experience of immaterial spiritual worlds. It is my argument that gift drawings make the divine immanent through intertwining strategies of materialisation and abstraction, a balance of representational modes that finds a precedent in European medieval uses of art objects to apprehend the sacred. Elina Gertsman’s 2021 publication Abstraction in Medieval Art: Beyond the Ornament forms a keystone in my approach to the gift drawings, both in its content and its methodological embrace of anachronism as a way to explore medieval art and vision from new angles.

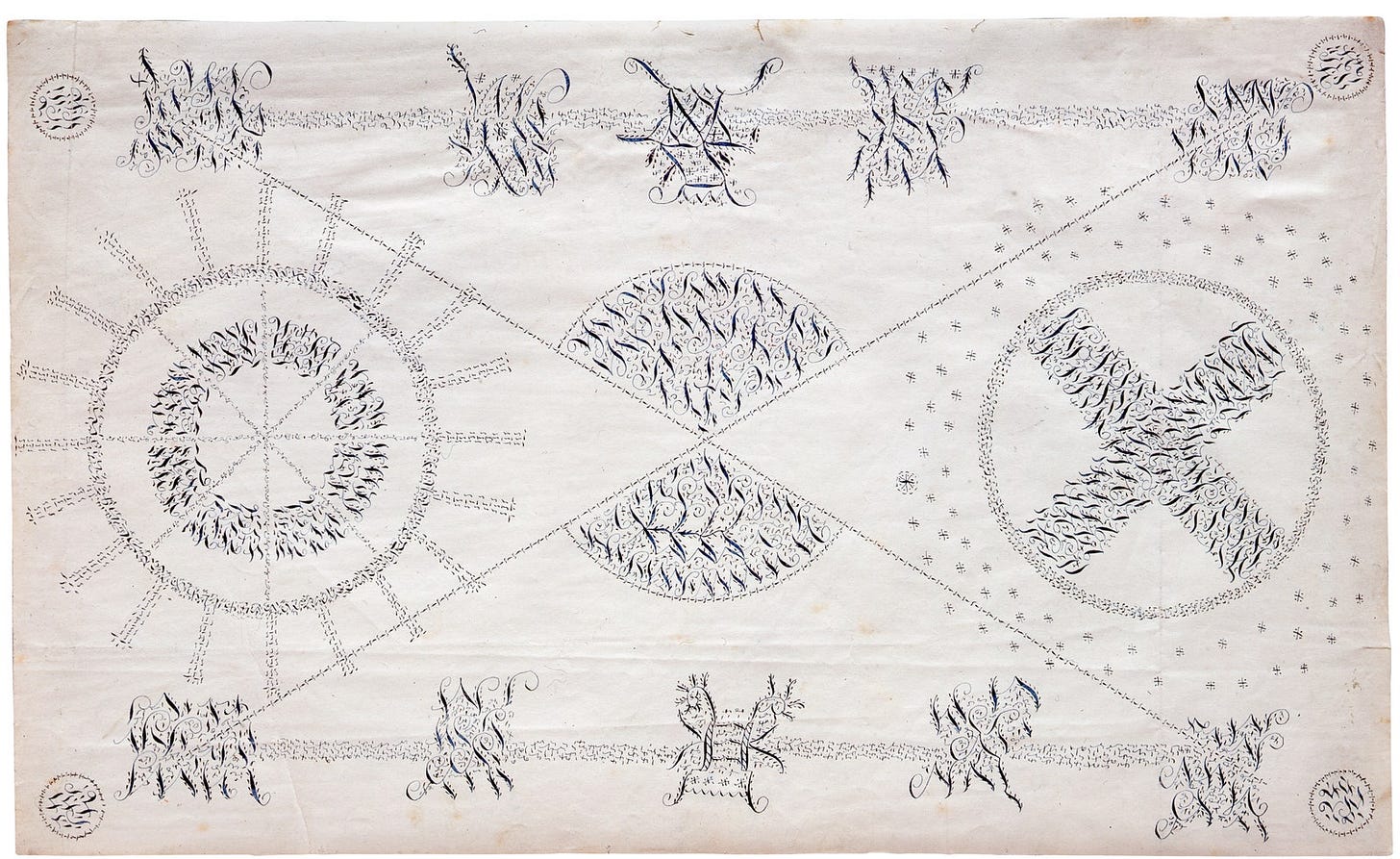

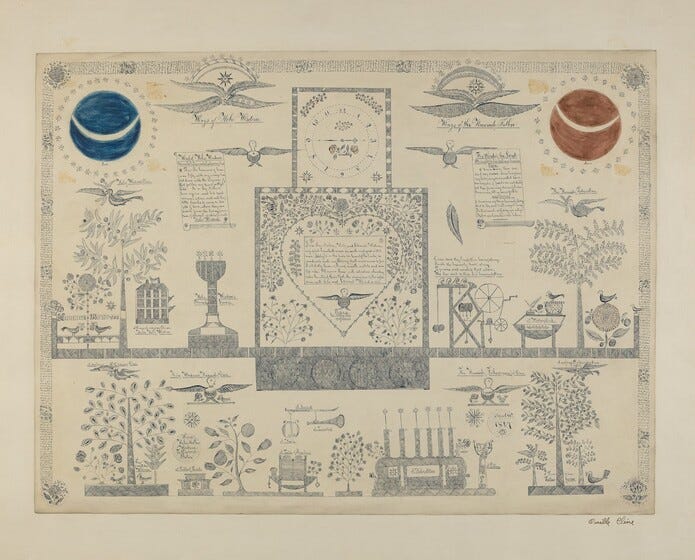

I have chosen two examples to focus this discussion around: Hannah Cohoon’s “A Little Basket Full of Beautiful Apples” (1856, figure 1), and Semantha Fairbanks and Mary Wicks’ “Sacred Sheet” (1843, figure 2). The former was an active member in the Shaker community at Hancock, MA; the latter two were based in Mount Lebanon, NY. Both drawings, in different ways, strain at the limits of what can be expressed on a page. While Cohoon’s drawing is invested with objecthood, behaving as a relic of visionary experience, the “Sacred Sheet” uses non-denotative forms to inscribe traces of the spirit world onto paper. These works are products of a rarefied, enclosed environment, and to approach them properly we must first understand their context. In addition to a brief outline of the status of gift drawings within recent literature, I will begin by discussing the period known as the “Era of Manifestations” that generated their production, before considering the environment of tightly prescribed aesthetic regulation from which they emerged.

*****

The proliferation of visionary communication in the Era of Manifestations emerged from a moment of crisis within Shakerism. Following the deaths of Ann Lee and her immediate successors Mother Lucy Wright (1796–1821), Father James Whittaker (1784–1787), and Father Joseph Meacham (1787–1796), the relationship between the sect’s living members and Lee’s foundational charismatic spiritual authority was under threat of weakening. As celibacy was one of the main tenets of the faith, Shakers relied upon conversion and the longevity of existing members’ commitment for the survival of their communities over generations. From 1837 to the late 1840s, Shaker communities in Massachusetts and New York experienced a dramatic spiritual revival, perhaps in response to the loss of charismatic leadership. The transmission of messages from long dead Elders, Eldresses, and other inhabitants of the spirit world through living ‘Instruments’ was not unprecedented in the Shaker faith; their openness to dramatic expressions of spiritual possession was a facet of the emergence of the ‘Shaking Quaker’ moniker and their split from the Quaker sect. The Era of Manifestations, however, was notable for the unusual intensification of the frequency, spread and impact of these communications. They began at Watervliet (New York), the first Shaker settlement in America, where a group of adolescent girls began to experience trances and ecstatic visions, as noted by Elder Henry C. Blinn:

Under the direction of spirit guides they were conducted from place to place, and these guides conversed with those in the body, through the entranced persons. Without premonition they were taken on a visit to the Spirit Land, and as children, in their simple way, related all that they had seen and heard…Attention was called to things not seen by the natural eye.”

Similar instances of possession began to proliferate in Shaker communities across New York, New Hampshire and Massachusetts, especially amongst the young; sometimes lasting hours or even days, visitations took diverse forms, from dancing, “whirling,” and song to aphasia, seizure-like contortions and catatonic immobility. As spirit visitations became more common, they were recorded, “copied with all the meticulous care of a medieval scribe.” Earlier gift drawings, executed in pen and ink, were often closely related to text, either through dense lines of script incorporated into the image or through the inclusion of hieratic characters that obliquely resembled writing. Our case study by Fairbanks and Wicks (figure 2) falls into the latter category. By 1856, the time of Hannah Cohoon’s “Apples,” text was a lesser participant in a bright, graphic pictorial scheme. Any awareness of or reasoning for this broad movement from text into image during the Era of Manifestations is obscured by the total absence of the acknowledgement of gift drawings in the meticulous historical records, diaries and inventories kept by the Shakers in Hancock, MA and Mount Lebanon, NY, from which the majority of surviving gift drawings emanate.

Gift drawings began to feature in discussions of Shaker art and life after their ‘discovery’ in the 1930s by Shaker historians and collectors Edward and Faith Andrews. Their 1969 monograph “Visions of the Heavenly Sphere” presents a somewhat mythologised account of their first encounter with the image format. They recount a “Sister Alice” of New England unearthing a paper from a chest for their benefit, telling the Andrews that she had saved it from kindling as a child and telling them that “if you had shown any evidence of levity in your response, I was prepared to keep it as mine alone. I would have known that ‘the world’ could not understand.” Andrews began to catalogue known drawings, which laid the groundwork for subsequent scholarship by folklorist Daniel W. Patterson who, in his 1983 “Gift Drawing and Gift Song,” expanded the list of known examples and did significant work on their attribution and the biographical details of their makers. Patterson also mounted the influential argument that the motifs repeated across drawings – including hearts, doves, fruit and flowers – were drawn from New England tombstones and needlework traditions. In 1993, Sally Promey emphasised the relationship of the drawings to Shaker theology using art historical analysis, which she built upon in the 2001 catalogue for the exhibition “Heavenly Visions: Shaker Gift Drawings and Gift Songs” at the Drawing Center in New York City, which also featured essays by decorative arts historian John Kirk and Shaker historians Mary Ann Haagen and Ann Kirschner. Promey, Patterson, and the Andrews arguably remain the key authorities on gift drawings as a standalone creative category; elsewhere, broadly, they are mentioned as subsidiaries in chapters of publications focused on the more familiar elements of Shaker life and design.

Promey attributes the greater emphasis on Shaker furniture and design in scholarship and the popular perception of Shaker culture to the “modernist reinvention” of the sect’s craft production. She argues that a desire to locate the genesis of Modern Abstraction in an American tradition led mid-century antiquarians and collectors to position American folk art, and the clean, utilitarian forms of Shaker design in particular, as forerunners of modernist aesthetics. As Promey notes, the profuse ornament and arcane religious iconography in the drawings rendered them the “least amenable” to modernist appropriation, leading them to be relegated to a somewhat secondary position. It is precisely this position – outside of the orderly world of straight-backed chairs, sleek trestle tables and peg-rails – that invests Shaker gift drawings with their subversive appeal. Often delicately ornamental and bearing a recurrent preoccupation with aspects of the material world in their imagery, execution, and language, gift drawings fit uneasily within the Shakers’ severely aniconic visual culture.

The visual landscape of Shaker communities was tightly regulated by the centralized doctrines of “Millennial Laws.” Pictures and paintings were denigrated as superfluities; the Holy Laws of 1840 “strictly forbid that there should be any engravings, sculptures, pictures or images, or likenesses, either of man, beasts, birds, or any living thing, or the likeness of flowers or inanimate things.” In instructions resembling sumptuary laws, bedsteads were to be painted green; floor stains were restricted to “reddish yellow” in homes or “yellowish red” for shops, and the style, color and number of clothing articles were prescribed by detailed instructions (figure 4). In the 1821 Millennial Laws, worshippers are reminded that “those are not the true heirs of the Kingdom of Heaven who multiply to themselves needless treasures of this world’s goods”; the next section specifically bans the use of “superfluous finished or flowery painted clocks” among a long list of disallowed “Fancy Articles” (figure 3). Perhaps the most immediately striking facet of gift drawings as a category is their tendency to contradict the injunctions laid down in these laws, not only through the fact of their status as heavily ornamented “pictures or images,” but also in the frequent inclusion of articles that directly contravene particular rules – flowery painted clocks, for example, repeat in drawings by Sister Sarah Bates (figure 4). Similar examples of decorated furniture recur across Shaker gift drawings, alongside “likenesses” of flowers, birds, hearts, trees, the moon and stars. This iconography reflects the preoccupation with material things apparent in the contents of the visions recorded by Instruments, featuring “robes, wreaths, satin slippers, handkerchiefs, gold chains, drinking-cups, pens, writing-desks, instruments of music, silver speaking trumpets, doves, singing-birds, lambs, baskets of fruit.”

How might we account for this contradictory approach to material things and their visual representation, within a society stridently opposed to the picturing or possession of worldly luxuries? We could place the material imagery of the Shaker Spiritual world into the Christian hagiographic tradition of equating saintly bodies with earthly jewels, especially in the context of the jewel-encrusted foundations of the Heavenly Jerusalem. This, however, does not work to explain the explicitly oppositional relationship between the strict regulation of decorative goods and the gift drawing’s celebration of them. Promey suggests that gift drawings were configured as a “new category of images”; rather than existing as illustrative pictures or paintings, condemned as superfluities, they were instead “windows” onto a world of spiritual treasure. In her view, by taking objects of desire out of the material world and recontextualising them within a spiritual one, visionary materialism and attendant gift drawings compensated for the restrictions placed on Shaker relationships to things. She argues that the image makers averted the danger of scopophilic pleasure through their representational styles, depicting objects as weightless, “deny[ing] the qualities of volume and mass associated with earthly things.”

While I concur with Promey’s analysis of gift drawings as a new category of images, acting as extensions of spiritual visions rather than simply illustrations of them, I contend her reading of representational styles, especially in later drawings that move further away from the text-based paradigm referred to earlier. When viewed in the flesh, Hannah Cohoon’s Apples (figure 1) make appeals to it: they are insistent in their physicality. The paper creases under the weight of the thickly applied paint – a feat, considering Cohoon was using ink and watercolor. Rather than creating the translucent washes we might associate with these water-based mediums, Cohoon layers and stipples concentrated pigment to evoke the dappled texture of apple skin, glowing with vitality. Each fruit possesses a thick, golden-brown outline and a straight black stem, formed with a muscular solidity that belies Promey’s notion of weightlessness. Other approaches to a sense of objecthood can be identified across other examples of gift drawing, particularly in the category of “cutout” gifts. Papers cut into the shapes of hearts (figure 5) or leaves (figure 6) took on the physical shape of the content the visions described, allowing the faithful to hold spiritual gifts in their hands in the very forms they took in the spirit world. Underpinning this logic is a closing of the gap between the actuality of the spiritual realm as experienced in visions, and its record or representation, a confusion of the two that is evident in written accounts from the Era. Church records from the second of June 1844 record as much:

The Elders informed us…that there would yet be something further given us as a notice from the Spiritual world, and a heart was given us with a promise that we should yet know what was written on them - the writing was now accomplished - and the presents were ready to be given out. The brethren and sisters then came forward, kneeling down and receiving the papers, in the form of a heart, beautifully written over with words of blessing in the name of the Father.

From this retelling – one of the only moments where gift drawings appear to be referenced – it is difficult to discern whether the hearts were perceived as emanating from the Spiritual world, or from the hands of living elders.

Together with the sanction on artwork or “pictures,” it is this confusion between supernatural visionary content and their manifestations as “material things that do exist on earth” (Stewart) that, as Promey notes, “forc[es] the creation of a new category” of image-making. It is my contention, however, that this “new” category finds its precedent in the Christian use of relics: objects that allow the faithful to access the divine through sight, not only by representing holy figures or places, but by embodying parts of them. Holger Klein’s presentation of the ontological between-ness of relics and reliquaries is useful here:

There exists a special category of things which function on a physical or sensuous level as well as on a spiritual or metaphysical one, things that not only transcend the boundaries between matter and spirit, earth and heaven, life and death, part and whole, but contain elements of both or collapse these categories altogether.

Just as relics make absent figures or places present through fragments, gift drawings perform as earthly manifestations of spiritual things: things that, like relics, “can be classified as neither pure objects or pure signs.”

*****

Where Cohoon mobilises ink and watercolour to give worldly presence to spiritual experience through hefty, material form, the shapes depicted by Semantha Fairbanks and Mary Wicks in their “Sacred Sheet” are dispersed and inchoate. Executed with precision in blue ink, three circles are bisected by two transverse lines; at the top and bottom of the image, a row of five thorny insignias are joined together by a stream of small chicken-scratch marks. There is no solidity here, but instead, a rhythmic modulation of space through the repetition of similar marks, schematically arranged. Bolder calligraphic strokes anchor hairline dashes which radially disperse and and condense into linear arrangements, instilling the drawing with a sense of pulsating contraction and expansion. When stared at for long enough, the drawing appears to be living. Jackson Arn, art critic for the New Yorker, beautifully articulates this active quality in his review of the current exhibition of gift drawings mounted by the American Folk Art Museum in New York City. He describes the Sacred Sheet as composed of “an endless wriggle of parts,” noting that “there are barely any solid forms or straight lines here, just licks doing impressions of both.” Arn identifies a similar sense of lively autonomy in Cohoon’s Apples, in his observation that “each fruit struggles for roundness but ends up caked and freckled in its own distinct way.” In comparison to Cohoon’s apples, the Sacred Sheet at first appears illegible, abstract, something emanating from a different part of Shaker vision and belief entirely. I would suggest, however, that the two images share representational strategies and motivations, even beyond their joint possession of a strange, vibrating life.While Cohoon’s work breaks down separations between vision and representation through an emphatic objecthood, the Sacred Sheet collapses spiritual and worldly realms by materializing the process of communication as it was felt.

The “Sacred Sheet” under consideration is one of a group of six similar works, commonly attributed to the same pair of Shaker women. One such drawing was marked as being “received January 25th 1843. Written in the 1st Order on the Holy Mount Febr 2nd 1843” (figure 7), leading Daniel Patterson to posit that this collection was generated as part of a dramatic session of communal worship also dated to January 25th, recorded in detail by Brother Giles Avery. During this service, “a sheet of clean white paper was handed…to an instrument” every half an hour, whereupon “the Holy Angel and our Heavenly Parents, likewise the Holy Saviour…wrote with their fingers their names upon the white sheet.” It is likely that this ‘writing with fingers’ was ideational rather than literal; Patterson notes the time between the dated drawing being “received” and “written,” a gap that occurred frequently, according to other gift drawing inscriptions.

Despite its probable execution after the communally witnessed visionary experience, our Sacred Sheet is marked by its conception within the Shaker meeting house. In its symmetrical arrangement of circles, crosses and diagonal lines, the drawing’s composition echoes the arrangement of bodies in space within the context of communal worship. An example of the careful arrangement of group configurations during services is demonstrated by “An Arrangement for Standing During Worship” (figure 8), a floorplan from New Lebanon. It demarcates the bodies of worshippers through dots evenly arranged in lines radiating from a central square reserved for the family elders; the concentric rows of worshippers are divided by two pathways, intersecting at the centre to form a cross. As John T. Kirk observes in his analysis of neoclassicism in the geometric vocabulary employed across Shaker living spaces, floorplans, furniture and dance configurations, dances during the Era of Manifestations struck a delicate balance between careful geometry and unruly physical expression. This balance between order and chaos is embodied by the Wicks and Fairbanks Sacred Sheet. The former is expressed through the symmetrical composition and geometric forms, as well as in the delicate, controlled articulation of the cursive flourishes. Even the small “licks” are even in their spacing and form. And yet — as in the mottled surfaces of Cohoon’s apples straining at the confines of the paper ground -– there remains a sense of frenetic energy. Curlicues appear to spawn flecks of ink, while the scratchy pseudo-script that runs along the upper and lower registers is scrawling and irregular. Through this admixture, the authors of the Sacred Sheet communicate the unruliness of visionary experience, scaffolded by the structure of Shaker orderliness.

In her preface to “Abstraction in Medieval Art: Beyond the Ornament,” Elina Gertsman frames the usage of non-denotative forms in Medieval religious art as a mode of “both withdrawing figuration and suggesting elusive presence,” arguing that abstraction is used to “signa[l] the unrepresentability of what is really at stake.” The abstract, script-like forms of the Sacred Sheet do just this: they act as inscriptions of numinous experience, laden with movement, language, and the arrangement of space, without rendering any of these components explicitly legible. Gia Toussaint’s citation of Christian Kiening on illuminated manuscripts is helpful in the articulation of this tricky mode of representation: for him, ornamented letters possess “an ontological symbolic quality. They convey a meaning which is not simply based on a relationship of reference, but on the suggestion that what is meant is present in the figure of the writing itself.” This “ontological symbolic quality” is at work not only in the abstracted Sacred Sheet, but also in Cohoon’s apples, especially in the components of it that are less directly representational. Below the apples, Cohoon writes “I saw Judith Collins bringing a little basket full of beautiful apples…from Brother Calvin Harlow and Mother Sarah Harrison. It is their blessing, and the chain around the bail represents the combination of their blessing.” Abstraction and materiality are intertwined; Tte staunch, caked apples are blessed by a fragile, wavering line of blue ink.

*****

As in the case of a saint’s relic and the reliquary that houses it, gift drawings give presence to that which is – to most – invisible or absent, mediating the immaterial through the sensory. While Hannah Cohoon’s Apples embody the elision of vision, object, and image present in a range of gift drawings and Shaker thinking surrounding spiritual communication, the jointly produced Sacred Sheet transcribes the illegible experience of spiritual possession as it was felt within Shaker worship. The division between strategies of abstraction and figuration are not straightforward, but rather, entangled: the abstract Sacred Sheet invokes the arrangement of Shaker bodies in Shaker space, while the fleshy thingness of the apples is accompanied by abstracted space and line. In both cases, aspects of the spiritual world are brought into proximity with the material one, strangely and imperfectly. In beginning to think through the complicated interpolation of material and spiritual things in Shaker gift drawings and Shaker life, Georges Didi-Huberman’s comments on representation and resemblance are a suitably gnomic place for us to end:

To resemble no longer means, then, a settled state but a process, an active figuration that, little by little or all of a sudden, makes two elements touch that previously were separated (or separated according to the order of discourse). Resemblance is henceforth no longer an intelligible characteristic, but a mute movement that propagates itself and invents sovereign contact like an infection, a collision, or even a fire.

Bibliography

Andrews, Edward Deming, Faith Andrews, and Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum. Visions of the Heavenly Sphere : A Study in Shaker Religious Art. Charlottesville: Published for the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum [by] the University Press of Virginia, 1969.

Crosthwaite, Jane F. (1989) ""A white a seamless robe": Celibacy and Equality in Shaker Art and Theology," Colby Quarterly: Vol. 25: Iss. 3, Article 6.

Déléage, Pierre “Pseudographies : The Revealed Script of Emily Babcock.” L’Homme - Revue française d’anthropologie, 2018, 227-228, pp.49-68.

Georges Didi-Huberman Confronting Images : Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art. (University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005

Foster, Lawrence. ‘They Neither Marry Nor Are Given in Marriage: The Origins and Early Development of Celibate Shaker Communities’ in Religion and Sexuality : Three American Communal Experiments of the Nineteenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.

Gertsman, Elina, ed. Abstraction in Medieval Art : Beyond the Ornament. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021

Kirk, John T. The Shaker World : Art, Life, Belief. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997

Koomler, Sharon Duane. “Shaker Gift Drawings.” Grand Street, no. 68 (1999): 112–17.

Manca, Joseph. Shaker Vision : Seeing Beauty in Early America. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2019

Morin, France, and Sally M. Promey. Heavenly Visions : Shaker Gift Drawings and Gift Songs. New York, NY, Los Angeles, CA, South Minneapolis, MN: Drawing Center ; UCLA Hammer Museum ; University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

Neal, Julia, and Daniel W. Patterson. “Gift Drawing and Gift Song: A Study of Two Forms of Shaker Inspiration.” Western Folklore 44, no. 2 (1985): 143.

Patterson, Daniel W. (Daniel Watkins), 1928-. Gift Drawing and Gift Song : a Study of Two Forms of Shaker Inspiration. Sabbathday Lake, Me. :United Society of Shakers, 1983.

Promey, Sally M. Spiritual Spectacles : Vision and Image in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Shakerism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press 1993..

Promey, Sally M. “Celestial Visions: Shaker Images and Art Historical Method.” American Art 7, no. 2, 1993): 79–99.

Sarbanes, Janet. “The Shaker “Gift” Economy: Charisma, Aesthetic Practice and Utopian Communalism.” Utopian Studies 20, no. 1, 2009. 121–39.

Seeman, Erik. “Native Spirits, Shaker Visions: Speaking with the Dead in the Early Republic.” Journal of the Early Republic 35, no. 3 (2015): 347–73

Soule, Sandra A. 2014. Shaker Cut-and-Fold Booklets : Unfolding the Gift Drawings of Emily Babcock. Clinton, N.Y.: Richard W Couper Press.